Essay: Adding Digital to the Jeweller's Bench

Essay: Adding Digital to the Jeweller's Bench

Melbourne jeweller Bin Dixon Ward is fascinated by the relationship between digital technology, jewellery and its maker. She discusses the development of 3D printed jewellery including her own work in this field.

3D modelling and 3D printing both play a central role in my own jewellery making. As a jeweller practicing at the beginning of the 21st Century, I am influenced by the forms, materials and tools of our times. Jewellers and crafts people have been experimenting with various 3D printing techniques for some time. Early significant users of the technology include Australian designer/maker Gilbert Riedelbauch with his fused deposition modelling brooches that celebrate the mathematical and layered origins of their making. Riedelbauch’s CSH brooch (2000) is printed with ABS plastic and finished with gold film deposition. Israeli industrial designer Ron Arad’s bangle Not Made By Hand, Made in China (2002), is made with selective laser-sintered nylon (a process where nylon powder is fused layer by layer with lasers); and asks us to consider the role of the machine in jewellery making. The ever-influential Dutch jeweller Gijs Bakker made the Porsche bangle (2002) using stereolithography, a process of curing resin layer by layer with light, demonstrating the possibilities of 3D modelling software to scale and manipulate forms.

In this instance, a status symbol is made affordable and wearable, a car scaled to be worn on the wrist as a bangle. Each of these pieces and their makers have had a significant influence on my jewellery making, not only because they use 3D printing, but also, more importantly, because the technology, as tool, is referenced in their materials, forms and the meanings attached to their works.

The next wave of artists to incorporate 3D modelling and 3D printing to realise their artwork, include Australian maker Mitchell Whitelaw, whose Measuring Cup (2010) presents 150 years of Sydney’s temperature records as a small beaker; and UK artist Geoffrey Mann whose Shine (2010) was made from a 3D scan of a traditional silver candelabra. The reflective surface confused the scanner. Unable to distinguish the reflection from the candelabra itself, the resulting 3D printed object included spikey shafts, materialising the immaterial. US ceramicist Michael Eden pays homage to Josiah Wedgwood’s role in the Industrial Revolution, and references the use of bone in porcelain in Wedgwoodn’t Tureen (2008). Taking the shape of the traditional tureen, the porous surface of this 3D printed vessel captures the structure of bone. For his Mellitus project (2010), Doug Bucci (US) collected data from people’s blood sugar levels (including his own) and via 3D and digital visualisation software created their ‘portraits’ over a particular period of time based on this biological information. Again, the appeal of these artists and their works lies in the way in which the capabilities of the digital design and manufacturing process is integral to the realisation of the work.

The relationship between the technology, the work, and its maker is at the centre of my practice and research. Working closely with the digital technology: the computer, its software, and 3D printer; I have come to understand it as a tool. Combined with my own knowledge, conceptual and physical skills, I can create objects that can both acknowledge their origins and express my ideas.

An angle of a building corner, a distorted reflection, a pattern on a pavement; these often fleeting visual experiences are the beginnings of ideas. Once I start to work with my ideas, I transform and develop them into objects using the tools of 3D modelling software (Rhino3D) and 3D printing. These tools come into play, and the idea has a chance of becoming a real world object.

In time and with constant use, my digital skills have become innate and unconscious. Hand–eye coordination is no longer a conscious activity, as manipulating tools becomes a part of my physicality. This is the tacit knowledge that Peter Dormer (The culture of craft, 1997) describes, but it is also the tool as prosthesis, as Donna Haraway (A cyborg manifesto: science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century, 1991) envisages. The mouse in my hand becomes a part of me as I move the object in the screen as easily as if it is in my hand, or as I would use a hammer or a pencil. I know my material and tools so well that even though the finished object is printed remotely and I will not be able to touch and handle it for a week or more, I know what it will feel like, how big it will be and what it might sound like. As a digital craftsperson, my intimate relationship with my materials and tools is at the heart of my practice.

The urban environment is a significant ongoing theme in my jewellery as I attempt to reflect the place in which I live, and which influences how I view the world and what I value. Most recently I have investigated the city grid, its history and its contemporary transformation into the digital grid, forming the basis of contemporary communication.

I’m interested in making objects that are reflective of the times and place in which we live, so it is no surprise that this technology appeals. Jewellery can act as a communicator of social, political and cultural themes. Where digital technology is used in the process of making, its presence can be referenced in its forms, materials and systems. In the same way that an Art Deco brooch might be identified by its curves and geometric forms, coloured gemstones or Bakelite, jewellery of the digital era reflects the materials and tools of the digital object. 3D printed objects act as a cultural artefact, reflecting the times and cultural identity of the wearer. The maker’s choice of materials and forms, and the wearer’s choice of material and form, speak of that which is valued at the time.

Bin Dixon Ward

Explore more on Object Digital

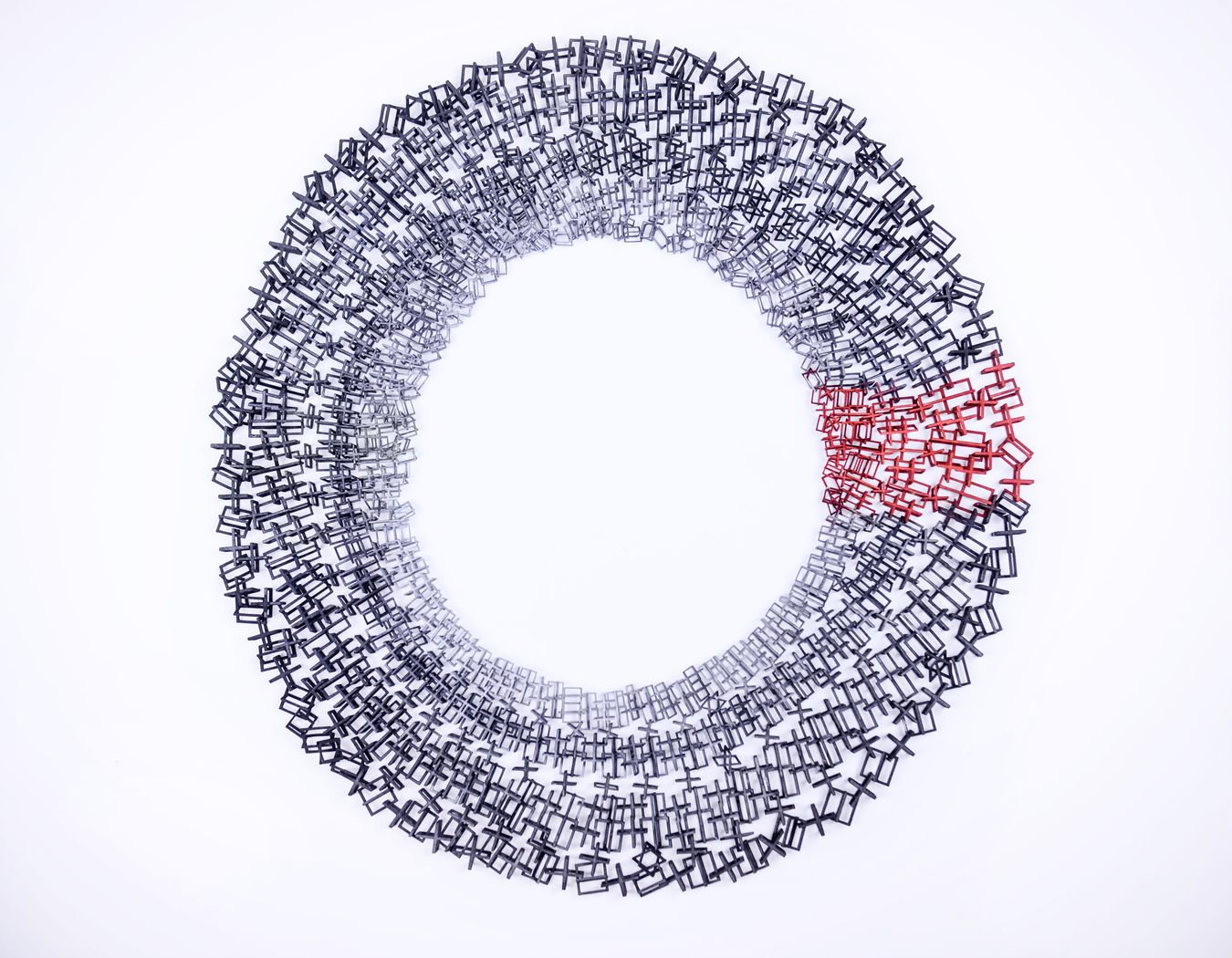

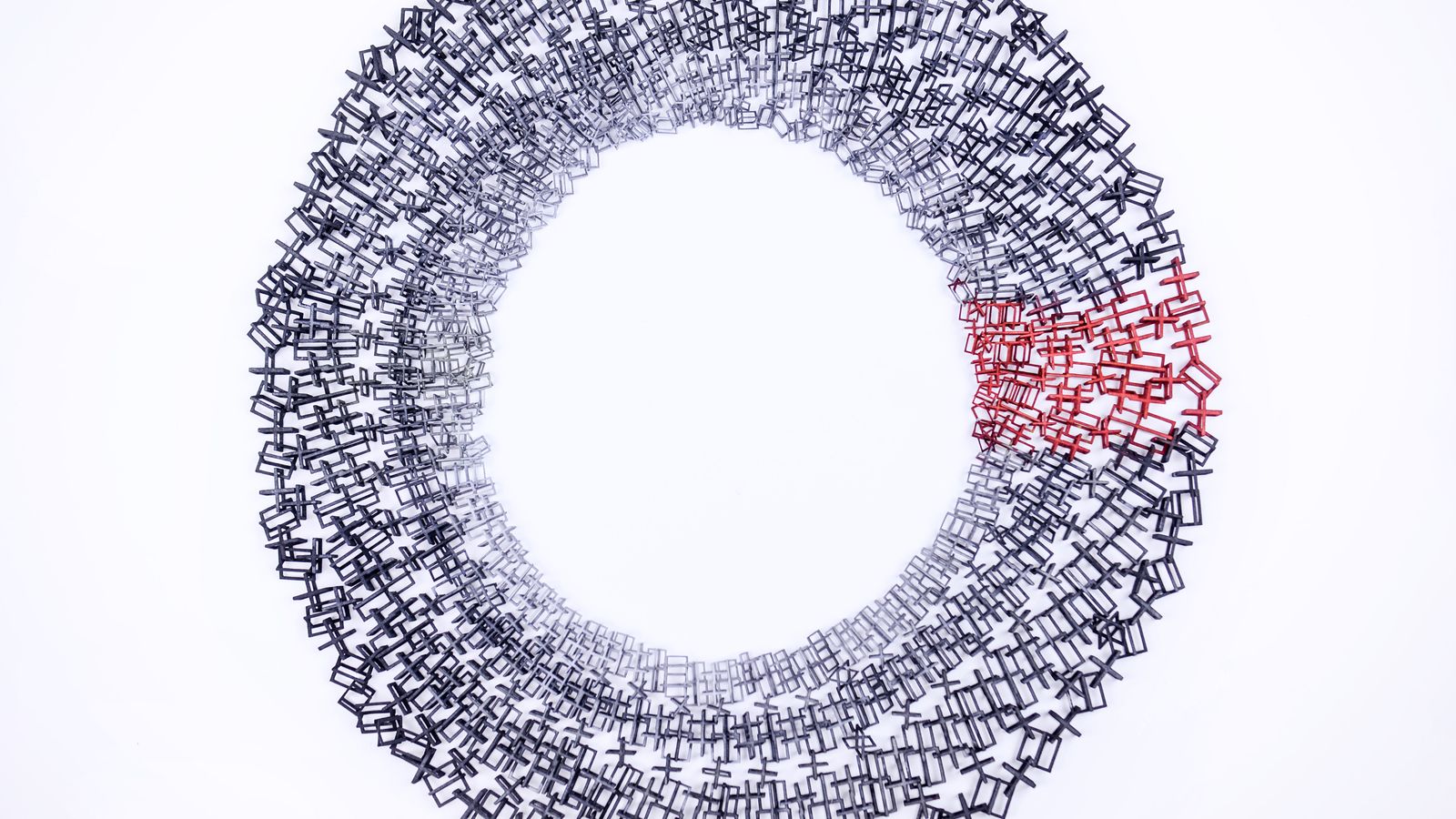

Image: Bin Dixon-Ward, 2017, Intersections, nylon, ink, 500 x 500 x 15 mm, photo: Giulia McGauran