Essay: Furniture Futures and the Promise of 3D Printing

3D printing has promised to significantly impact the way objects are realised. Berto Pandolfo, an industrial designer and Senior Lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, examines the evidence that this prophecy is coming to fruition.

Nearly every typology of object has been touched by 3D printing; from toys to spacecraft, from food to architecture and from medical prosthetics to hair pins. Additionally, the variety of materials and processes has expanded as the promise of 3D printing continues to drive research, innovation and creative enterprise. 3D printing is used on a micro scale and in large scale printing; it is used by expert scientists and engineers in the world’s most exclusive laboratories, and in the homes of everyday users. This democratised technology has enabled creative professionals the ability to work on projects that not long ago would have been impossible, and one particular product group with a rich and long history that has received considerable attention has been furniture.

It has been more than a decade since French designer Patrick Jouin designed the first one-piece 3D printed chair. More recently, new materials and processes are inspiring designers around the world to explore the ever-changing boundaries of furniture design. Finnish designer Janne Kyttanen is a 3D printing pioneer and in 2015 he added to his impressive collection the

Sofa So Good. This one-piece sofa, designed with a complex lattice structure, is 3D printed using Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) in plastic and then metal coated. It is lightweight, uses very little material and is structurally sound. Unfortunately it retails at 100,000 USD. In 2016 Kyttanen’s most recent piece is Avoid, Rhodium, a small 3D printed table that is rhodium plated, with a design inspired by spatial geometry theory. In the same year, British based designer Daniel Widrig designed the Little Bit chair printed in concrete, while Joris Laarman from the Netherlands, another internationally recognised 3D printing guru, presented his latest experimental sculptural work Butterfly, a room divider constructed from 3D printed bronze.

While 2016 may be regarded as a year of exclusive and limited-edition pieces, projects generated in 2017 manifest an attempt to address issues beyond form and aesthetics. Rotterdam-based research and design studio The New Raw designed and developed an urban furniture solution that is 3D printed from waste material. My own project, MND (manual ‘n’ digital), investigates the notion that desktop 3D printers are capable of producing parts for furniture with structural integrity and favourable cost and material efficiencies. Consumer level printers have now reached a stage where they produce parts that are structurally appropriate for use in load bearing situations – like the legs of a small side table. I also wanted to highlight the beauty that is inherent in raw 3D printed parts that are so often hidden beneath

a coat of paint or lost entirely through sanding. The visible layers and the slightly imperfect nature of the bonding, represent a fragility that should be celebrated. MND was also about co-locating parts made by machine and parts made by hand. It characterises an opportunity to work simultaneously across traditional craft methods together with cutting edge technologies.

Realistically impacting on traditional manufacturing is a common goal for researchers, designers and manufacturers operating in the 3D printing sector. Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and furniture manufacturer Steelcase, together with designer Christophe Guberan, address the scale and time limitations placed on current 3D printing technologies with their process Rapid Liquid Printing (RLP). This involves printing inside a mass of gel, thereby removing the limitation imposed by gravity. Without having to work up designs layer by layer like traditional 3D printing methods, RLP allows the printing of objects to happen significantly faster and as large as the machine will permit.

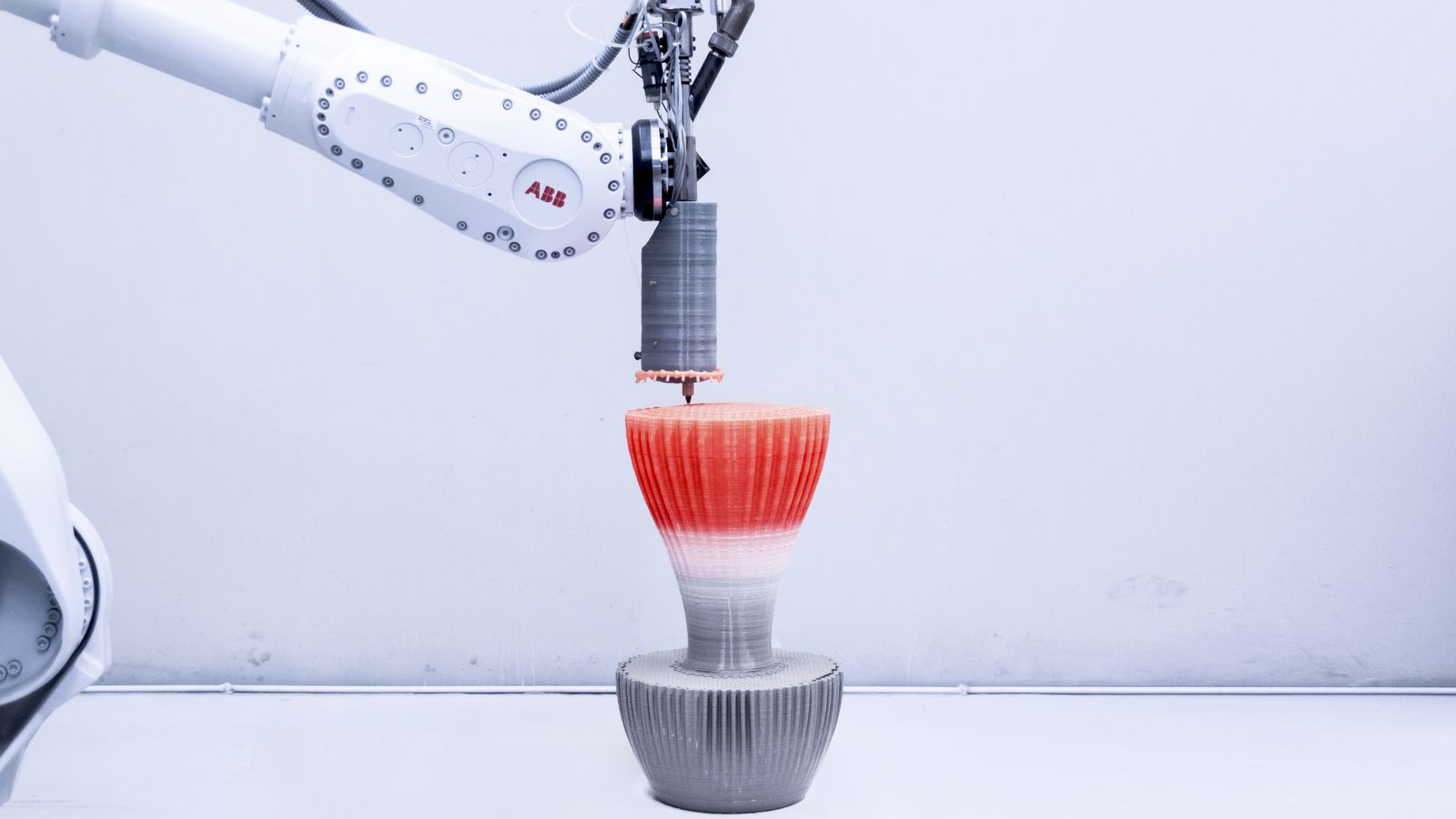

An example of applied 3D printing impacting on commercial activity was demonstrated by Spanish company Nagami which was established to explore how new technologies can shape future manufacturing. They have moved beyond 3D printing statement pieces useful for branding and marketing to the commercialisation of designs by internationally recognised designers such as the Robotica stool by Ross Lovegrove which is commercially available for the not-so-outrageous price of 2,450 EUR.

Two projects from 2018 focus on manipulating the mathematical data that is the digital model used in 3D printing. American designer John Briscella applied algorithms to digital models of iconic chairs from Eames and Saarinen to investigate how 3D printing might challenge conventional design processes. And Italian furniture company Driade have reinterpreted classic designs by Enzo Mari, Philippe Starck and Naoto Fukasawa, reimagining them for futuristic extra- terrestrial environments.

Technological advancements that will impact on future 3D furniture design originate from the United States. The Morphing Matter Lab at Carnegie Mellon University has developed a unique type of plastic that when exposed to a change in temperature will modify its shape. This plastic can be 3D printed into flat shapes and when exposed to heat will evolve into its final form, suggesting that 3D printed flat pack furniture is on the horizon. The process is known as Thermorph and can conveniently be used on desktop 3D printers. The Self- Assembly Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) together with researchers from BMW developed the Liquid Printed Pneumatics project. This innovation enables inflatable (airtight) structures to be 3D printed. Interestingly, on the 50th anniversary of the iconic Blow inflatable sofa from Zanotta, this may signal a revival in lightweight air-filled furniture designs.

One of the major trends in 3D printing relates to scale; printers as big as buildings are printing buildings and microprinters are printing micro structures one tenth the size of a human blood cell. This type of development will continue to impact on processes, materials and software, yet the promise to significantly impact on how we make things is still only theoretical or marginal at best. Realistic and applied examples that target mainstream object making are yet to materialise. However, given the growth, development and increased awareness that has occurred over recent years, although we may not be printing all our object needs in the future, the systems that currently provide society with physical goods (manufacturing) will undoubtedly experience considerable change.

Berto Pandolfo

uts.edu.au/staff/berto.pandolfo

Explore more on Object Platform

Image:

Ross Lovegrove, 2018, Robotica, photo: courtesy of Nagami; Berto Pandolfo, 2017, MND, photo: courtesy of the artist