Essay: The Lacemaking Practice of Rowan Panther

This text was written by artist Rowan Panther for a public program event as part of the exhibition, Deep Material Energy II.

kia ora, firstly I want to give a little background on who I am, seeing you are all new faces to me. I live in the Far North of Aotearoa with my husband and my dog. Photography was my first creative pursuit, lacemaking really snuck up on me. I am an artist but more than that, I am a maker. Makers have an unspoken connection to each other that’s hard to describe, and it’s probably based on the obsession with continually creating and producing. My work has developed slowly over time and is a continual exploration into my own cultural identity. I use bobbin lace as a medium in which to explore my cultural background within the wider context of identity negotiation and the future possibilities of traditional crafts. I make adornments aiming to convey belief systems, reinforce values and to focus identity.

New Zealand is a country with a rich cultural environment, it also has a difficult colonial backdrop, not unlike Australia. In this contentious setting I didn’t feel like there was anything out there that represented me… and I desperately wanted that.

My tūpuna or ancestors, come from somewhere else.

One common trait they all had was the courage and daring needed to set out into the unknown and try for a new life. I like this idea of returning to my ancestors to find my strength. I make pieces that look back to where I come from to inform where I could be in the future. I use the past to help me understand who I am.

My whakapapa (genealogy) originates from Ireland, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Samoa. Sometimes it feels like a forever unfolding mixture.

Here, I just want to acknowledge the pain this redistribution of people has caused, bringing its sovereignty and colonialism. We often think of colonisation of something from the past, however it is still very present.

It has only been through showing my work and having conversations that I have truly realised how this sentiment of displacement resonates with so many other people. This idea of identity negotiation not being fixed, but fluid and changeable. Belonging is a constant theme throughout my work, my own belonging primarily, but in that exploration, I create a space to welcome others to question and untangle their own sense of who they are, and where they fit. The pieces I make draw from this hybrid, then in turn, weave together diverse textile traditions.

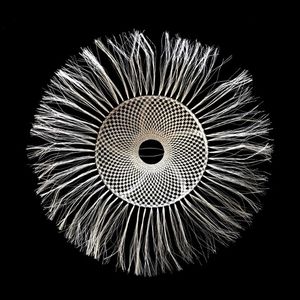

There is something about taking different practices and mixing them up to create something new that intrigues me. The lace patterns reference European designs such as collars worn by nobility, while the objects draw upon Pacific cultural forms such as ceremonial breast plates worn by chiefs. This results in adornments that entangle both colonial and craft narratives.

The materials I chose to make from are my foundations, Muka links my work undisputedly to Aotearoa. While the hard elements speak of other places, woods native to Europe and shells from the pacific.

Muka is the long filaments that run the length of the Harakeke leaves. Harakeke is commonly known as New Zealand flax, although it is in fact completely unrelated to the European flax plant. The Harakeke plant and the fibre is integral to Māori practices and traditions and has been for many years. There are a lot of different varieties, and each has a best purpose, whether it is for clothing, fishing nets, baskets or kete (a traditional Māori basket), the list goes on. Because the plant has such significance and symbolism, respect and protocol must be followed when harvesting. It’s important to acknowledge the gifts from the whenua (land) and the atua (ancestor/gods/spirits), especially now when we tend to take so much for granted.

Honouring the environment from where we draw our raw materials is important. Natural offerings are collected, crafted, and shaped into vessels that hold the lifeforce from where they originated.

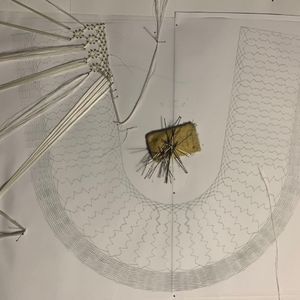

Muka is an unconventional lacemaking material and is particularly demanding. The threads are not twined like the long spools of thread more commonly used for linen or cotton bobbin lace; they are only as long as the blades of harakeke they are prepared from. Being too rough causes breakages and too delicate distorts the pattern so instead of 'using it' you have to work with it.

I feel inspired working with practices that are centuries old, that carry a wide, rich history of their own. To represent the tradition of lace I am re-presenting it from a new angle. Lace can be traced back in various applications centuries. I am fascinated by this tradition and a handing down of legacy. This is why I stick to established forms and patterns; it feels like you have direct contact with the lacemakers of the past.

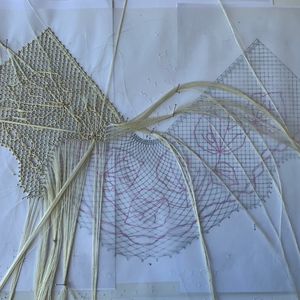

It’s a bit of a process looking at a sampler lace pattern and reinterpreting it. I prefer to use pencil and paper rather than employing computer programs. Drawing them up myself gives insight into how to proceed and where the tricky areas are hiding.

I have a very systematic way of working. It’s very process based. You start at the beginning and work methodically through to the end, with no surprises or changes. Lace is laborious. There are no shortcuts and using an unorthodox material adds another layer of complexity. If I added sampling on top, the length of time to make one piece would just be too time consuming. So instead, I rely on faith and forethought. Because I keep the pins in until the last, I am not guaranteed the end result is what I had in mind, you don’t know for sure what you have until the end when the pins come out and you trim everything back and lift it up off the cushion. Which is nerve wracking, especially when you have deadlines and have put months in. All you can rely on is your skill and planning.

The subject of time is recurring in my work. Even if it’s more of a product than a dedicated theme. My practice is underpinned by my level of personal investment. A means to display the dedication, not only the learning and practice needed to master traditional skills, but the time taken to conceive and construct individual objects. I hope that when people look at what I do they can see all the effort I have put in and feel a direct connection to my passion.

I find it hard putting a monetary value on my work. The fibre for the main body, being produced literally from my back yard, does not have a quantifiable value. I do use precious metals such as silver but as a functional addition that varies piece to piece. The material I use to convey my story, costs me nothing.

When I was putting this together, this is what I initially wrote, that my work costs me nothing. Then I pictured all the experiences I have missed. Time with friends and family I have turned down getting work ready for an exhibition or squeezing it in around and between paying jobs. The actual cost of working this way flashed through my mind. But I think we always being reinformed by what we do. Even when you write your artist bio again and again and think you know what your work is about.

This is on a more personal note, but my Dad passed away last year. A total shock, he had a heart attack. He was here, then he wasn’t anymore. And now I can see the true value of time. I have always felt a little like, when it comes to jewellery and adornment, nothing is more valuable than gold. Now months on without my Dad, I can see that something is more valuable than gold. Time. And the time I put into my work is the greatest gift I can give.

As part of the Deep Material Energy show here today, I have three adornments on display. Fa’afetai is the largest of the three. Fa’afetai is thankyou in Samoan, this piece serves as a thank you to family, those here and those who have moved through, and a thank you to life, both the joy and the heartbreak. I thought about my Dad a lot as this piece was coming into being. Fa’afetai stands as a symbol for the foundations, support and guidance gifted to us from our ancestors, both long passed and those which are more recent. Although we have our relationships and this aroha (love) to lean on, I also wanted to demonstrate the weight we must all carry as individuals. The notion the older a shell the more weathering and disease it accumulates is directly relatable to what it means to be human. It is the hard times in our lives when we seek protection the most that forms who we are and who we will become. But we must frame this pain with beauty. Muka is extremely strong yet appears so delicate. I often find myself having to dig deeper to find the strength I never knew I had, but it is always there.

Lua and Tolu can be viewed as siblings, the same but different, mirroring each other while also displaying their contrasts, reverently balancing their strength and fragility. I titled them in Samoan, introductory words to a new language, while offering a distinctly visual European influence. Here is that opening to explore the diverse combinations in which we are all made up. Honoring our individual whakapapa, past present and future.

Deep Material Energy II is presented by Australian Design Centre and supported by Creative New Zealand and Toi Rauwhārangi College of Creative Arts, Massey University, Aotearoa, New Zealand.

/https://adc-2-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/Picture_8.f638b14.jpg)