Object Podcast Series 3 Episode 5: Johannes Kuhnen

Series 3: Behind the scenes of MAKE Award: Biennial Prize for Innovation in Australian Craft and Design

Episode 5: Johannes Kuhnen, Finalist in 2023 MAKE Award.

Show notes

Host Lisa Cahill chats with master metalsmith Johannes Kuhnen.

Johannes is one of the pioneers of anodised aluminium jewellery. In this episode, Johannes explains why he actually finds anodising annoying, and his design process.

Hear from judges Jason Smith, Hyeyoung Cho and Brian Parkes on his MAKE Award entry, Remnant Green.

Johannes Kuhnen is one of Australia's most well recognised silversmiths. Johannes' practice has remained at the forefront of innovation, in particular his pioneering use of anodised aluminium. A fascination with the colour options of the aluminium continue to provide inspiration for his work and have also inspired many others to explore such potential.

Transcripts

Word document: TRANSCRIPT Object Podcast S3 Ep 5 Johannes Kuhnen

PDF: TRANSCRIPT Object Podcast S3 Ep 5 Johannes Kuhnen

Guests

- Johannes Kuhnen

- Jason Smith, Director and CEO of Geelong Gallery, Victoria

- Hyeyoung CHO, Chair of the Korea Association of Art and Design, and expert panel member of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize

- Brian Parkes, CEO at Jam Factory, Adelaide, South Australia

Show highlights and takeaways

“It's all in my head” [0:05]

For artist Johannes Kuhnen, the creative process is deeply rooted in his mind. He conceptualises and envisions his work mentally before physically creating them. This mental visualisation allows him to intricately plan every aspect of a piece, from its overall shape to tiny details.

“Sometimes I wake up at night and I can actually go through the whole piece and how I make it.”

Mixed feelings about anodising [1:40]

Johannes has mixed feelings about anodising. He admits that he doesn't love the process, describing it as “highly irritating and time consuming”.

He adds that when you anodise, you have a fairly high failure rate, saying “It's the frustration of that it doesn't always turn out as perfect as you wanted it to be.”

It’s also a process that takes a long time, he says.”It's about three hours between cleaning the piece and getting it out of the steamer or the boiling water at the end.”

Why Johannes Kuhnen turned to anodised aluminium [2:00]

Johannes trained in Germany in contemporary jewellery. He began using anodised aluminium when the price of gold spiked, making it too expensive for his jewellery.

He was also drawn to the possibility of incorporating vibrant colours into his work.

How he got started with anodising in the late 1970s [2:30]

At the recommendation of his jewellery teacher, Friedrich Becker, Johannes Kuhnen bought a do-it-yourself anodising kit. It had five litre plastic tubs, “a little bit of acid and a really cheap battery charger. That's all you need to anodise with.”

His art school bought the kit, and Johannes added 70 litre tubs to the set up, and got started.

Small tubs led to segmented vessels [3:30]

Johannes says it was the constraints of the equipment he was working led to new design solutions. To go bigger than the dimensions of an anodising tank, “I had to make small pieces and put them together,” he says.

“That was the start of segmented tray and vessel forms.”

A pioneer [3:40]

In the late 1970s, nobody else was anodising aluminium for jewellery. Johannes knew of one other artist in the UK, Pierre Degas.

Pierre didn’t do the anodising himself but was able to use commercial anodisers in England.

“Whereas I had to set it up and try it all by myself. “I was one of the first guys who did it. So basically I was a pioneer.”

Workshop 3000 [4:30]

Upon arriving in Australia, Johannes heard there was an open access jewellery workshop called Workshop 3000 where he could hire a bench while waiting for his tools.

During his time at Workshop 3000, Kuhnen engaged in piecework for conventional jewellers. He also received a commission from artist Susan Kohn to anodise two bangles.

“And Susan Kohn ever anodises since” .

‘Satisfies the Australian definition of a piece of art’ [5:45 ]

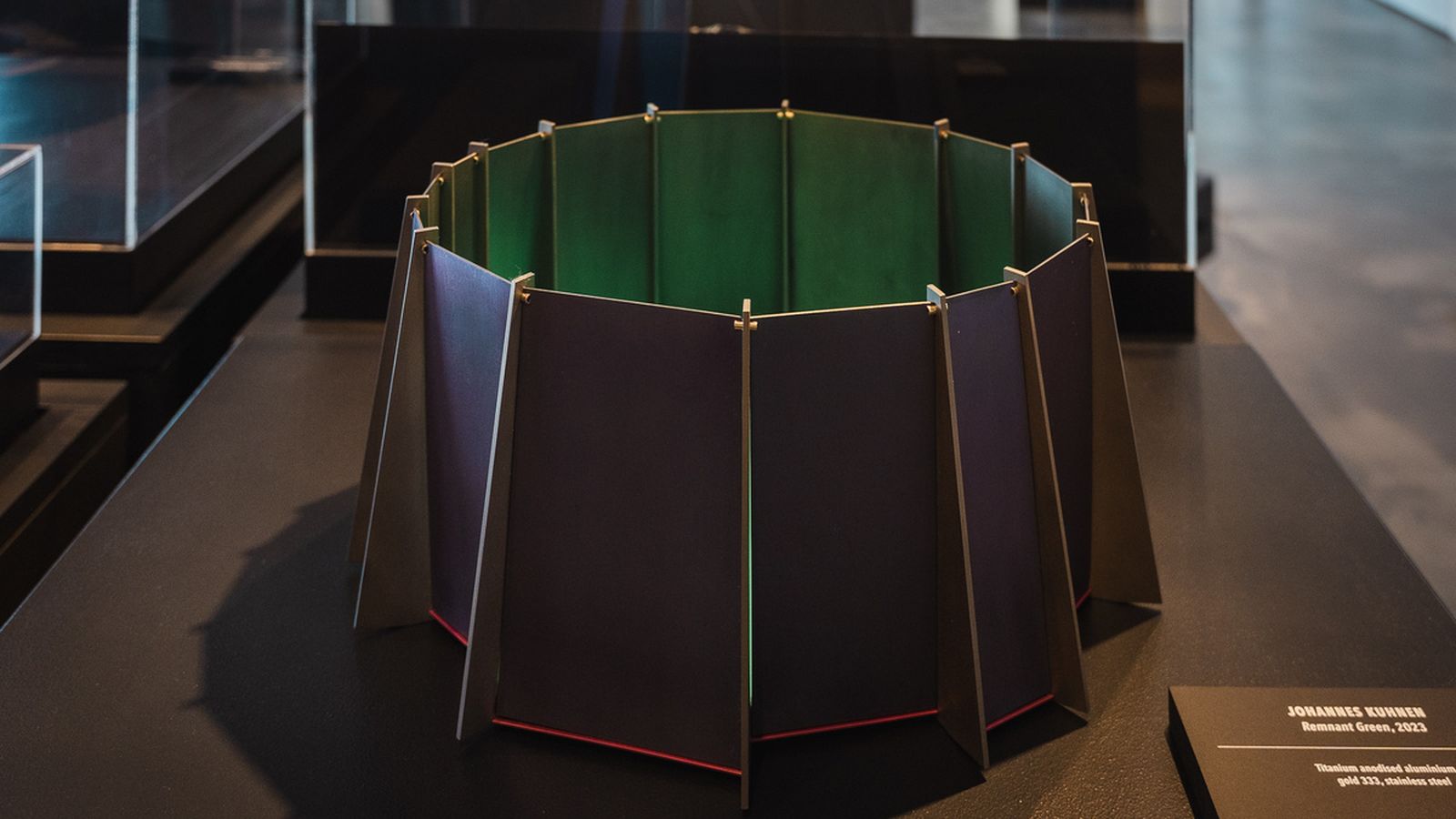

Remnant Green is a vessel form, which Johannes says cheekily, “satisfies the Australian definition of a piece of art. It will not hold water. It will leak. So it can be art. It's not functional.”

He describes it as “in one way a bit of a basket because it's a jagged oval with buttress blades that come up with a three millimetre thick titanium.”

The voids between these buttresses are filled with thin anodised titanium sheets, and create a reflection of the aluminium base plate. Johannes admits that “my titles are sometimes a bit flippant.”

Jason Smith, MAKE Award Judge [8:10]

Jason Smith, CEO and Director of the Geelong Gallery, says Remnant Green is particularly beautiful and remarkable in its scale for hollowware or metalwork. He highlighted the uniqueness of the work and praised its geometry. Smith noted that as one moves around the object, the colour changes due to the complexity and sophistication of the anodizing process.

Jason also remarked on the scale of the work as impressive, especially considering the challenges of working with anodized aluminium and intricate geometrical forms.

Intellectual approach [9:05]

Johannes takes an intellectual and conceptual approach to his work. He says he wants to explore things like “a form, arrangement of forms, arrangement of colours intersecting lines.”

“I don't work emotionally.”

Using CAD for metal work design [10:35]

Johannes Kuhnen uses Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software as part of his creative process.

He collaborates with an assistant (one of his former students), and gives her instructions for the CAD work. He specifies details such as the shape, arrangement of forms, colours, and the intersection of lines.

The CAD drawing is essential for precision in cutting materials like titanium. Johannes sees the process as a “mental arithmetic exercise”.

Once the design is complete, he uses digital cutting methods such as laser cutting, waterjet cutting, or wire cutting for greater accuracy in bringing his designs to life. In the case of Remnant Green, waterjet cutting was used to cut the titanium segments.

Hyeyoung Cho, MAKE Award Judge [11:15]

Hyeyoung Cho emphasises the exceptional concept and technique of Remnant Green. She notes the distinctive approach Johannes took in interpreting the material through geometry and colour. She highlighted the work's worldwide recognition and described it as a ‘one of a kind’ piece that stands out for its innovation in design and contemporary craft.

Innovation [12:46]

Innovation in Remnant Green is an extension of Johannes’ exploration with segmented tray and vessel forms. His early training in contemporary jewellery under Friedrich Becker, a renowned goldsmith, emphasised the importance of innovation.

“From the first day, he instilled in me that you had to be innovative. Innovation was everything. He didn't accept anybody's work if it didn't have a level of innovation.”

Brian Parkes, MAKE Award Judge [13:50]

Brian Parkes says that Remnant Green has a unique combination of earnestness and joy. He talks about the seriousness in the making process but also noted the playfulness in the geometry and colour,

Brian recognises Johannes’ influence as not just a maker and artist but also a thinker in the craft and design space in Australia for several decades, and his contribution to contemporary practice of craft and design.

Winning awards and buying new tools [14:50]

Johannes talks about the practical benefits of winning awards in his career, like where award winnings allowed him to buy tools and materials.

In 1972, he bought a set of rolling mills with prize money from an award. Johannes points out that the financial support from awards, particularly in fields where materials and tools can be expensive, allows artists to reinvest in their work.

CREDITS

Object is a podcast of the Australian Design Centre. Object is produced by Jane Curtis, in collaboration with Lisa Cahill. Sound engineering is by John Jacobs.

Return to Object: stories of design and craft main page