Essay: Beyond Pretty

The possibilities of contemporary jewellery

Myf Doughty explores the work of contemporary jewellery designers Susan Cohn, Julia deVille and Kyoko Hashimoto in this essay, included in NGV publication She Persists: Perspectives on Women in Art and Design.

For as long as humans have been engaging in cultural and symbolic practice, the making and wearing of jewellery and body adornments have been central to the expression of identity, status and values. From indigenous communities, guild systems, and religious and regal production to contemporary designer-makers and multinational corporations, the result of 100,000 years of being is a design discipline as layered and complex as human culture itself. The stratification of the practice has seen jewellery’s symbolism and cultural significance morph over time – preserved, adapted and co-opted. It is in the grey areas – the points of divergence where meaning, interpretation and value can be challenged, the status quo questioned and new ideas suggested – that contemporary jewellers flourish.

Relative to the long history of jewellery production, it is only very recently that jewellers have positioned themselves as cultural commentators rather than the often-obscured tradespeople. In the fifty years from the 1920s to the 1970s, social, political and cultural upheaval and change swept the world. After the ravages of the Second World War, art, architecture and design became testing grounds – offering opportunities for reflection and also for hope. They provoked audiences and proposed radical new ways of seeing and being. Technological advancement spurred a desire to throw out the old and embrace a new future. In this climate, the design and production of jewellery in Western cultures began to shake loose from guild systems and trade-based markets. Jewellers were trained in art schools, and artists began to explore jewellery as a medium for nuanced and deeply personal expression. By the 1960s, contemporary jewellery had moved away from its industrial roots and was focused on reappraising itself, by confronting and subverting its own historical conventions to engage in new discussions about power, privilege and preciousness.

In recent times, contemporary jewellery has been experiencing another shift. An age of global instability, ‘fake news’, international climate emergencies, rising inequality, mass migrations and a polarisation of politics has fostered renewed impetus for designers and artists to take a position and challenge audiences to engage with the issues of the time. A growing number of contemporary practitioners have moved beyond the critique of historical context, materials and stylistic tropes that defined contemporary jewellery of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Instead they are engaging with the deeply personal and political nature of the medium to question the actions, beliefs and values at play in the world, and also, significantly, revealing themselves in their work by sharing their own stories and perspectives. They employ techniques of critical design, a term coined in 1999 by Anthony Dunne to define an ‘attitude’ or ‘position’ rather than a methodology.1 Critical design leverages design language to cultivate a critical sensibility in designers and consumers. The goal is to actively question and challenge the norms and dominant narratives that guide how we interact with and interpret the world around us.

By harnessing design as a form of social critique, contemporary jewellery designers such as Susan Cohn, Julia deVille and Kyoko Hashimoto respond to the dynamic shifts in consumer culture and contemporary life. Whether under the banner of critical design or not, these practitioners are openly taking a position on issues they see as important, and using the intimacy and significance embedded in their discipline to challenge the viewer to engage with these issues as well. By recasting established meanings and traditions, their works create a dissonance with what has come to be accepted or expected as ‘jewellery’ or ‘design’.

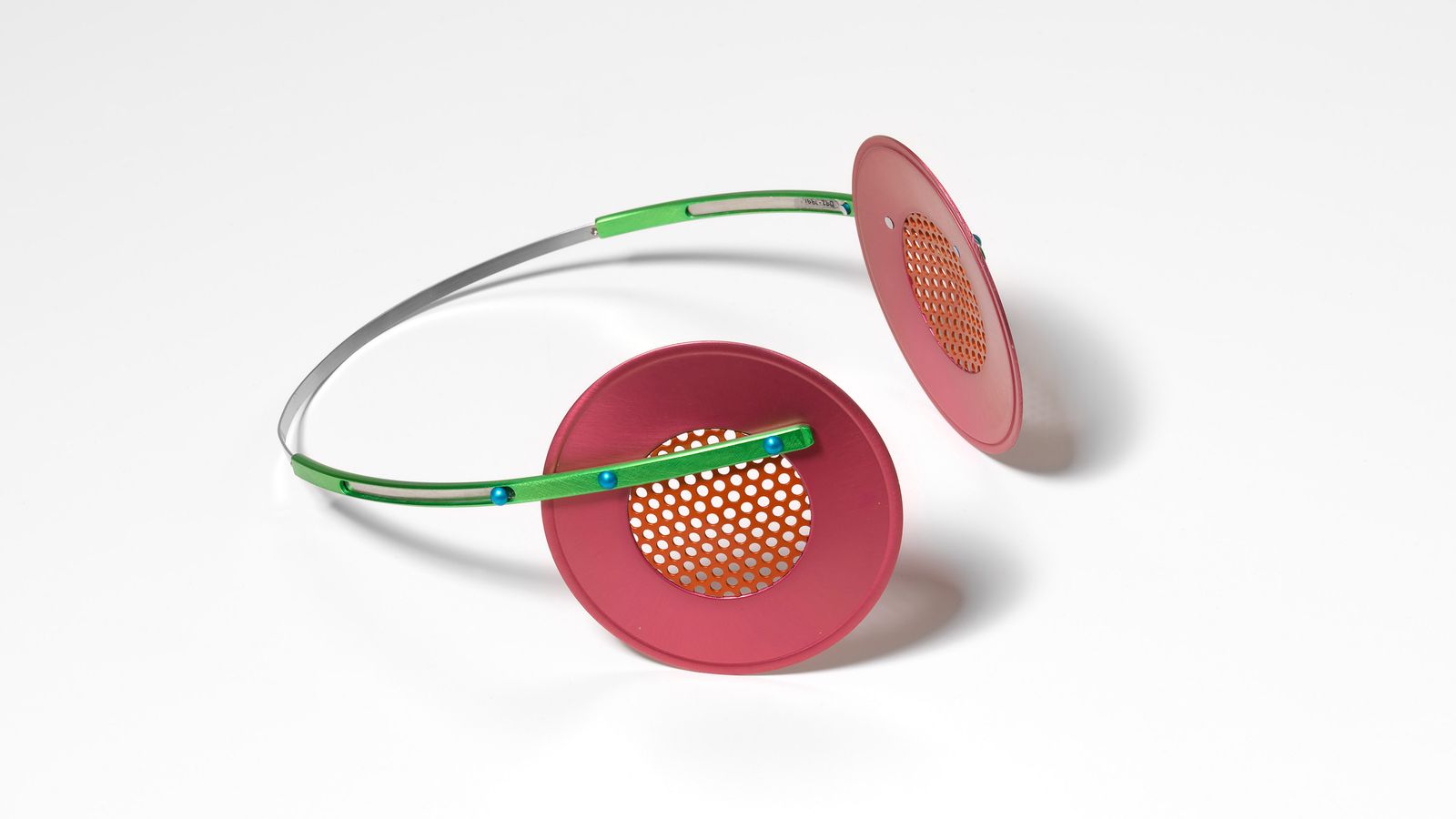

Sydney-born Susan Cohn founded her Melbourne studio, Workshop 3000, in 1980, and creates works that explore and foreground the embedded politics and power in the making, wearing and reading of jewellery. Cohn has a particular sensitivity to the symbolic and functional roles of jewellery, particularly in relation to identity and belonging. Security pass, access all areas, 1989, and Walkman, headpiece, 1984, highlight the fluid relationship between an object’s functionality in the practical sense (headphones for listening to audio, for example) and in the symbolic sense (aligning with particular subcultures or telegraphing particular values). The latter, Cohn posits, is constructed by the wearer through the build-up of layers of interaction between the wearer and observers as the object’s history grows over time.

In the ensuing decades, Cohn’s work has become pointed in its interrogation of the politics of jewellery as it reflects personal story and experience. Last the blast, 2006, is a utilitarian pendant made from a stainless steel casing that protects two titanium tags containing important information about the wearer and a message for loved ones. The materials and form are such that the pendant should survive in the event of a bomb blast, allowing the wearer to impart a final message to their family. Cohn designed and produced this piece after she saw grieving parents on television, explaining how they had nothing left of their daughter who had died in the 2002 Bali bombings. Last the blast engages with the global scale and complex brutality of terrorism through personal storytelling and the intimate gesture that jewellery offers.

Cohn’s performance-based project Meaninglessness, 2018–19, offers a new avenue to confront the politics of jewellery through storytelling and conversation. The project was a reaction to Danish legislation passed in 2016 that allows border authorities to seize ‘meaningless’ jewellery (in other words, jewellery that does not have sentimental value) from people seeking asylum to contribute to the cost of their processing.2 The suggestion that jewellery could be meaningless, or that a government agent ignorant to the life of someone else’s jewellery could make such a judgement, highlighted a breakdown in sensitivity and the understanding of how value and sentiment are ascribed.

Meaninglessness is centred on the telling of Cohn’s own story, of her ancestors’ migration from Japan and Europe, her time living on the street and her charting a career as a jeweller. In this, she reaffirms the importance of respecting the meaning and intent of different people and their stories through adornment. Cohn encourages her audience to reflect on their own experiences of connection, of loss and politics. While telling her story, Cohn makes pins based on a single leaf of the four-leaf clover, symbolising courage, love, trust and hope. These are then gifted to members of the audience, concluding the performance with an act of hope and generosity – forging new connections and the future histories of stories to come while also emphasising jewellery’s role as a teller of past histories. The performative nature of Meaninglessness departs from a traditional understanding of contemporary jewellery as a medium, but in its intent it exemplifies the push for contemporary practice into a realm of critical engagement between practitioner and their audience.

New Zealand–born, Melbourne-based contemporary jewellery designer and taxidermist Julia deVille revels in this realm of design. Her work is a paradox: it aims to shock the viewer but at the same time provoke quiet contemplation. Blurring the boundaries between art, design and jewellery, deVille pairs taxidermied animal carcasses (she prepares these herself from animals that have died of natural causes) with her elegant and intricately made jewellery, often set with valuable gemstones such as diamonds and rubies. DeVille artfully plays to the ostentation of Renaissance, Baroque and Victorian aesthetics. She draws out associations with Victorian-era memento mori, mourning jewellery and stately precious stones, while at the same time agitating for contemporary issues, particularly animal rights.

DeVille’s It’s a wonderful life, 2012, is a protest. Instead of being conveyed via a placard or slogan, the message is presented by way of a stillborn calf, 959-carat pyrope garnets, 1946-carat cultured garnets, freshwater pearls, 6.3-carat rubies, 25-carat uncut diamonds, sterling silver, and 18-carat white gold, among other historically precious materials. The calf is suspended from the ceiling as though it has been freshly slaughtered and left hanging in the abattoir. Strings of beautifully set pearls and gems drip from the neck like blood and are arranged to collect in a glass milk bottle below. DeVille states, ‘It commented on the bobby calves in the dairy industry. They’re taken away from their mothers at a few days of age as they’re considered waste product. It’s a symbol of the actual cost of conventional milk’.3

Presenting jewellery divorced from the human body draws into question whether this can be considered ‘jewellery’ at all. The tension this creates in the work only adds to its power. The combination of luxury jewels and slaughtered calf is macabre and arresting. It unsettles the familiar associations of jewellery and the grandeur of Renaissance and Victorian art and adornment by inserting a sense of brutality, forcing the viewer to look again in order to make sense of the story being told.

Offering a more subtle but equally effective approach to contemporary jewellery, Japanese-Australian designer Kyoko Hashimoto taps into the intimacy and talismanic power of jewellery to critically engage with ideas that extend beyond the realm of daily human contemplation. Her Coal musubi neckpiece, 2019, reflects on the disparity between the significant geological timescales involved in natural production of coal (300 million years) and the rapid pace with which it is unceremoniously extracted and burned to generate electricity and produce steel. In this piece, Hashimoto has retrieved coal from the Sydney Basin and painstakingly turned it on a lathe, forming perfect black spheres. Each sphere is gently cradled in a kangaroo-leather pouch tied using a Shinto knot known as a musubi, a symbol of human reverence for the natural world or union between people. The delicacy with which Hashimoto treats the coal honours and respects the ancient origins of a material typically regarded as cheap and dirty. Coal musubi neckpiece is an example of how Hashimoto’s work channels the capacity for jewellery to act as a medium for contemplation and otherworldly reflection. The sombre materiality can be read as a memento mori to coal, suggesting a future where it is no longer a resource for burning but a resource for decoration.

As with traditional instruments of personal divination and mourning, the power of Coal musubi neckpiece lies not in extravagance or the use of expensive materials but in the quiet relationship to the body. Prayer beads, pendants, charms, lockets and rings are all designed to be handled often and kept very close – slipped under clothes, held against the chest, cradled in the hand or dangled from the wrist to offer a tangible connection to intangible concepts.

Hashimoto identifies as a critical designer. She is harnessing the physicality and familiarity of jewellery to create a powerful platform to foreground the social and environmental implications of unfettered material consumption, and to confront her own contributions, and those of the design industry more broadly, to a material culture that is proving ecologically disastrous. As Hashimoto observes:

Jewellery has this incredible, long history related to the notions of preciousness, power and status. Yet what the field of contemporary jewellery has done is to flip these values on their head and question the very notions that they are built upon … My position [as a critical designer and maker] is to illustrate where things come from, how they are made, and where they end up.4

Ritual objects for the time of fossil capital, 2018 (in the NGV Collection), which Hashimoto designed and produced in collaboration with designer Guy Keulemans, continues her exploration of the way we engage with and understand materials as primary resources that are extracted from the earth. Each piece is made from broken plastic toys encased in a concrete composite material and carved into three neatly finished tools of Buddhist ritual. Hossu 払子 (brush), Hōhatsu 宝 (bowl) and Juzu 数珠 (beads) directly reference the forms and functionality of these deeply symbolic objects. Hashimoto explains:

It was a commentary on how easily plastic toys break and become obsolete … considering the millions of years it takes for petroleum to form under the surface of the earth from algae and zooplankton. Then [that material] is made into a crappy plastic toy that breaks in an hour! The transformation of the broken plastic toys into Buddhist objects is to reflect on these timescales.5

Re-creating these sacred tools in ubiquitous materials associated with mass-produced, often low-quality design creates tension between the Buddhist conception of relative time, life and enlightenment and the contemporary realities of mass consumption, perception of value and consumer awareness.

The desire to harness the language and power of design to encourage deeper thought, a second glance or heightened sensitivity to the machinations and ecosystems at play in the world is an important part of critical and contemporary design. Susan Cohn, Julia deVille and Kyoko Hashimoto are among many designers that are reshaping the way jewellery can be used to voice ideas and challenge the status quo. Synthesising the deep history, embodied meaning and physicality of the medium, contemporary jewellery persists as a vital force of cultural production and influence.

Notes

[1]

Anthony Dunne, Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience and Critical Design, RCA CRD Research Publications, London, 1999.

[2]

Al Jazeera & agencies, ‘Danish MPs approve seizing valuables from refugees’, 27 Jan. 2016, Al Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/01/danish-mps-vote-seizing-valuables-refugees-160126055035636.html, accessed 20 Oct. 2019; AFP/The Local, ‘Here’s how Denmark’s famed “jewellery law” works’, 5 Feb. 2016, The Local, https://www.thelocal.dk/20160205/heres-how-denmarkscontroversial-jewellery-law-works, accessed 20 Oct. 2019.

[3]

Ben Morgan, ‘Julia deVille’s life after death’, 13 Feb. 2013, We Heart, https://www.we-heart.com/2013/02/13/julia-devilles-life-afterdeath/, accessed 3 Aug. 2019.

[4]

Myf Doughty, interview with Kyoko Hashimoto, 22 July 2019.

[5]

ibid.

She Persists: Perspectives on Women in Art and Design is published by NGV and available for purchase at the NGV Shop https://store.ngv.vic.gov.au/products/she-persists-perspectives-on-women-in-art-design

Further content is on the NGV website https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/channel/she-persists/

Read more on Australian contemporary jewellery with ADC On Tour exhibition Made Worn: Australian Contemporary Jewellery including four essays, A Well-Worn Country by Kevin Murray, Material Investigations by Penny Craswell, Constructing Identity by Margaret Hancock Davis and Everything and Nothing: Jewellery Beyond Adornment by Melinda Young.

Image: Susan Cohn, Walkman, headpiece, 1984, anodised aluminium, stainless steel, 17.1 × 16.5 × 7.6 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Kyoko Hashimoto, Coal musubi neckpiece, 2019, coal, vegetable tanned kangaroo skin, eucalyptus wood, waxed linen, 25.0 × 25.0 × 4.0 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne