Essay: Constructing Identity

Jewellery is powerfully connected to identity. Margaret Hancock Davis writes about how jewellery can affect the wearer and how contemporary jewellers express their own identities.

"Contemporary jewellery is never about how much a piece cost. A design can be emotive, intellectual or simply make a powerful statement … It's also about self-awareness and how a certain piece makes you feel about yourself and how you want the world to see you.”1

Jewellery is a signifier. When it is worn it provides clues to the wearer’s identity: membership of a cultural group, interests, a rite of passage, social status or even age. Individual body adornment can go as far as enabling society to structure and control the behaviour of its members or allow society to celebrate with pride, in its differences.

Just this weekend I was reminded of the power of jewellery and its ability to shift one’s energy, how your mood or sense of yourself can be impacted when we wear a certain item of jewellery. I am lucky enough to own one of Blanche Tilden’s spectacular Graded Palais Necklaces. This necklace is large, even Blanche has noted that when she first made it that she wondered about its scale, but it is exactly the necklace’s scale that I love. It sits perfectly on me. The Graded Palais demands attention, you feel quite empowered when you wear it. It is bold, it strikes out confidently, but it also has an implied fragility to it. Made of borosilicate glass and sterling silver, when worn its beautifully articulated form adjusts and moves with your body, capturing light and creating a gentle tinkling sound. But there is always this underlying unease I feel, the sound reminds you of its materiality. I can’t help it, I don’t want to break it, it’s made of glass. Possibly this necklace reveals more of me than I plan to tell. Sadly I don’t wear it enough. I really should wear it more, it is truly wonderful.

This is in part how a wearer’s identity can be expressed through jewellery, but how does a maker express identity in their own work? Is it the same in the making as it is in the wearing? In Made/Worn: Australian Contemporary Jewellery, contemporary jewellers and visual artists express ideas of identity in a multitude of forms and grapple with how identity is formed, controlled and expressed. They ask us to consider many questions:

How do jewellery or objects of adornment express connection between people? How can a jeweller speak of their time, and question practices around them? How can jewellery capture a fleeting moment, an expression of place and time viewed by a maker? If jewellery is seen by some as superfluous, an added decoration, a luxury, how then can one critique the modern predicament, particularly when using finite resources? How do we define Australian culture? What does it mean to be within this society and how might we define ourselves? When living in a society saturated with messages, what messages should we tune ourselves into? How is language manipulated, can we also manipulate language?

Through the works of five of the exhibitors, we look to how the personal is interpreted and developed in their work.

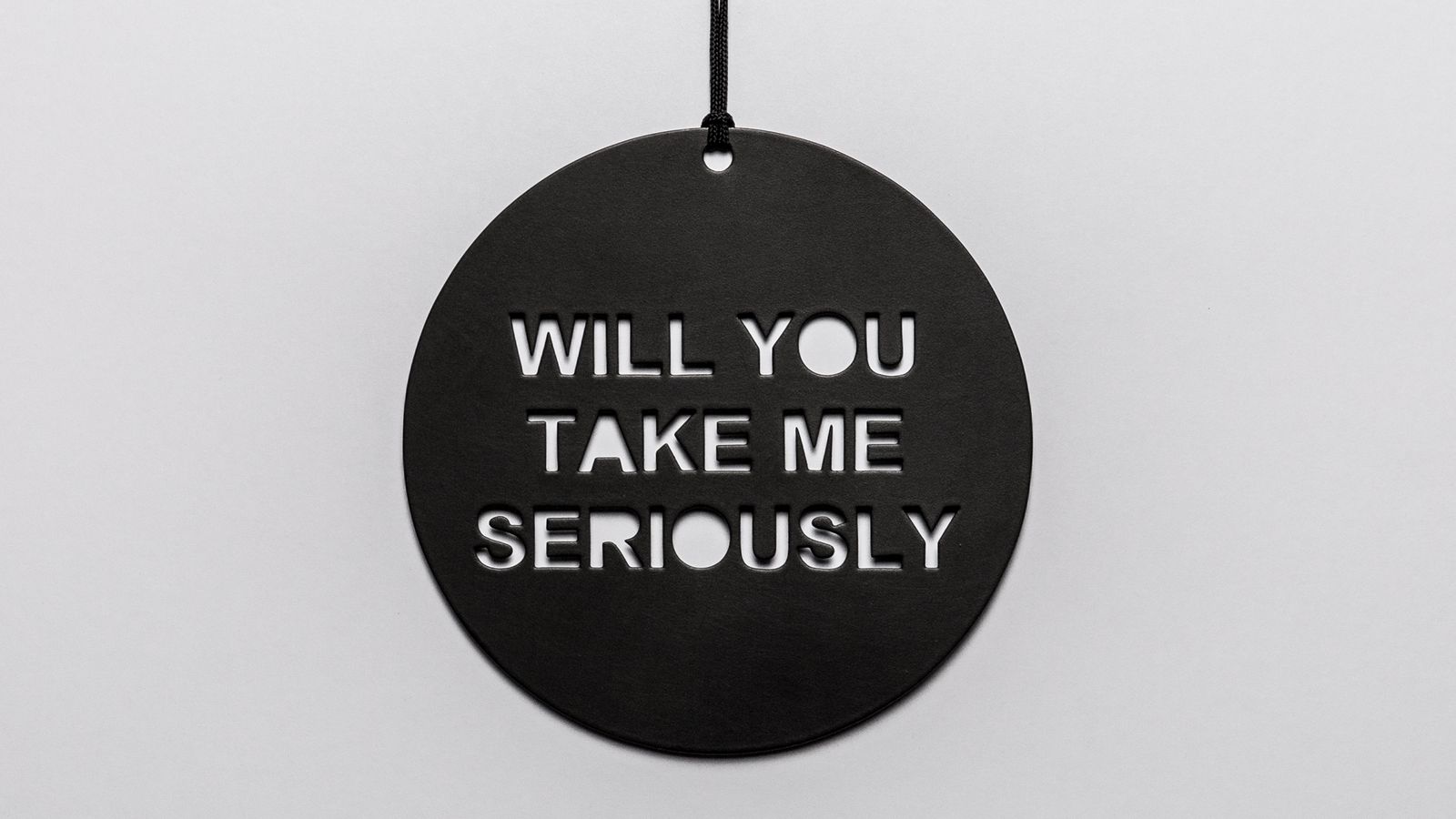

I see the possibility in the mundane, everyday throwaway statements. I collect, examine and remove them from conversations and build text into signs. I like to draw upon the ambiguity of language, of the numerous readings and associations that any word may possess, as well as how the meaning changes when a work moves wall to body and back again.2

Based in the rural New South Wales, Zoe Brand’s jewellery practice could be seen as an antithesis to her surrounds. Using the tropes of signs, billboards and the ready-made, Brand’s text-based jewellery practice is about interaction, connections and the underlying performative nature of jewellery. Here jewellery isn’t just a signifier, it literally is a sign. With common everyday phrases pressed into metal or etched and printed onto Perspex, Brand sets us the challenge to reconsider her chosen phrase’s meaning, and how this meaning may a shift as different people wear the work or it is viewed in different contexts. These text-based works are a means by which Brand is able to critique gender politics, consumerism, value, all be it with a wry smile. For Brand as a maker she is “always interested in hearing how [her] pieces are interpreted, and whether the owner settles on a more concrete meaning to the work or continues to leave open their understanding or reading of the work.”3

In the past I have made works about my identity, and looking at who I am, what makes up who I am, my identity, for instance my heritage, the society I belong to, my family and the knowledge that has been handed down to me.4

Liam Benson is a Sydney based performance artist who works in video, photography and textiles. Playing with symbols of nationhood, royalty, and popular culture, Benson uses his body as the site of adornment to respond to the identity politics at play within Australian Culture. Benson focused much of his earlier work on his own identity as a queer, white male. The works presented in Made/Worn, Coat of Arms and R.E.S.P.E.C.T both from 2009, date from this earlier part of his career, and speak of the hybrid nature of identity.

Having been based at the Parramatta Studios, in recent years, Benson practice has expanded to consider the culturally and linguistic diversity of the community he is embedded within. As Benson notes, Western Sydney “embraced me – it made me fall in love with it”.5 From 2015–18 Benson created three collaborative works through a series an ongoing workshop project that brought communities members into the studio, creating works that spoke of differing voices and a shared view of Australia. The results were: Participatory Community Embroidery: You and me (2013–17), a sequined map on silk organza that uses AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia6 as a reference point; Participatory Community Embroidery, Untitled (flag) (2017), a deconstructed Australian flag in which Benson posed the questions what would you like to add or what would you remove from this flag; Community Participatory Embroidery, Thoughts and Prayers (2015–2018), a flower wreath in which each individually stitched sequined and beaded flowers was dedicated by the sewer to someone special as a means to remember them.

I have always made work about memory and in a way my fear of forgetting. I hold people and memories dear.7

Jess Dare is an Adelaide-based jeweller and object maker who works primarily with powder-coated non-precious metals and flame-worked glass. In recent bodies of works, Dare has been influenced by a residency she undertook in 2016 in Thailand. During her residency, Dare received training in the art of Phuang Malai (floral garlands).8 For Made/Worn she presents Making Time, a meditation on the act of giving between mother and child.

In this work we are presented with a series of pendants, each pendant is a recreation of a natural gift presented to Dare by her son Banjo. Alongside the pendants are small photographs of the original seed pods, twigs, and flowers presented to Dare while in larger format images we are shown the moment of exchange as Dare’s hand gently holds out the newly rendered facsimile meeting Banjo’s hand offering up the original treasure.

In many ways this series can be seen to invert the ideas of Phuang Malai, as Dare is deliberately making permanent the offering of ephemera. These beautiful works hold us, they draw us in to our own tender memories of being a child. The quiet moments of collecting treasure with wonder. They are a small offering. They capture a moment, a memory of exchange, of sharing, of giving and receiving love.

Communicating a sense of wonder triggered by something often unnoticed, discarded and ordinary is the guiding themes in my practice.9

Moments in time are also integral to Inari Kiuru’s jewellery and object practice. Rather than the fleeting gestures and moments of connection between people Kiuru look to the ephemeral wonder of the natural world. Finnish-born and Melbourne-based Kiuru credits her Scandinavian childhood with developing her keen sense of viewing the subtle variations in nature.

Taking to the streets of Brunswick, Victoria, Kiuru records the gentle shifts of light, changes in seasons, and great cloudscapes juxtaposed against the rigid built environment on camera, before recreating these captured moments within her sophisticated brooches. Conjuring an array of readily-accessible industrial materials: concrete, steel, pigments and mica to create richly surfaced works that subtly shimmer when worn. Her choice of materials echoes her subject matter, industrial materials infer the urban environments while mica and pigments reflect the tonal shifts and fragility of the natural world. To Kiuru these works “are a constant revelation of something I call ‘home’”.10

What I make is completely informed by discarded materials. This provides a constant challenge as I am presented with a plethora of used and unwanted things that behave in different ways. A further challenge is to employ creative practices and techniques that endeavour to create no further waste.11

The natural world is where Melbourne-based contemporary jeweller Pennie Jagiello finds inspiration. However, this is a natural world that has been interrupted, interfered with, or is in decline.

Jagiello’s practice is firmly located in the ‘now’, critiquing the current environmental calamity we find ourselves in. Working with anthropogenic marine and land-based debris12 that Jagiello has extracted from environments as vastly different as the Pilbara in Western Australia, to the coastal regions of Victoria and New South Wales, she employs plaiting, binding, knotting, and sewing as a means of combining and connecting materials. It is a conscious decision by Jagiello not to use metal fastening techniques, as a further means to minimise the impact of her practice.

The importance of my work is placed within human-made debris as the discarded wearable heirlooms we pass on and leave behind us, in place of more traditional forms of jewellery. Diamonds are forever, so is anthropogenic debris which defines in our short existence the era and errors of the Anthropocene.13

I believe jewellery as heirloom is a possibly perfect place to finish a discussion of jewellery and identity. The material artefacts we pass on signify to others where we place value, they speak to our judgements, our ideals and our interests. Through jewellery, future generations, as with the current generation, can glean information about and insight into both the maker and the wearer.

Margaret Hancock Davis is the Senior Curator at JamFactory in Adelaide.

Made/Worn: Australian Contemporary Jewellery is an Australian Design Centre exhibition that includes the work of 22 contemporary artists working in Australia now. Find out more here.

[1] Scott, K, 2013, Treasured Perspective: The value of contemporary jewellery lies in qualities more elusive than straightforward monetary value. https://www.smh.com.au/money/treasured-perspectives-20130713-2pwra.html

[2] Brand, Z, 2018, https://www.contour556.com.au/zoebrand

[3] Brand, Z, 2019, artist’s statement of intent for Made/Worn, 2019.

[4] Benson, L, 2018, Community participatory embroidery project - facilitated by Liam Benson. https://vimeo.com/235472590

[5] Benson, L, 2018 in Mudie-Cunningham, D, 2016 ‘Working Class Man (Now Famous): Liam Benson. Sturgeon Magazine, Issue 6.

[6] The AIATSIS map is an attempt to represent all the language, tribal or nation groups of the Indigenous peoples of Australia.

[7] Dare, J. Thailand residency: A string of flowers – a sequence of event, 2016. https://garlandmag.com/article/thailand-residency-a-string-of-flowers-a-sequence-of-events/

[8] Phuang Malai literally translates into “bunch garland”, an ephemeral craft employing different patterns and flowers for different meanings and occasions.

[9] Kiuru, I, 2019, artists’ statement of intent for Made/Worn.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Jagiello, P., 2019, https://australiandesigncentre.com/madeworncontemporaryjewellery/pennie-jagiello/

[12] Jagiello defines anthropogenic debris as human-made materials thar have been discarded causing serious negative environmental impacts.

[13] Jagiello, P., 2019, https://australiandesigncentre.com/madeworncontemporaryjewellery/pennie-jagiello/

Image: Zoe Brand, Will you take me seriously? (detail), 2015. Photo: courtesy of the artist.